Originally published in PREA Quarterly Magazine

Housing prices have increased in 2020 and 2021 at some of the fastest rates seen in many years. Inflationary pressures have been felt most in the single-family sector, as the multifamily market was negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in some areas. Although the pandemic exacerbated many of these inflationary trends, a fair number were already present before the pandemic started.

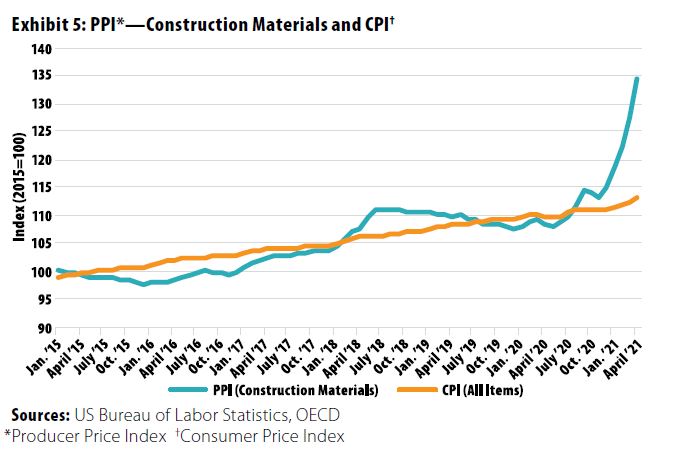

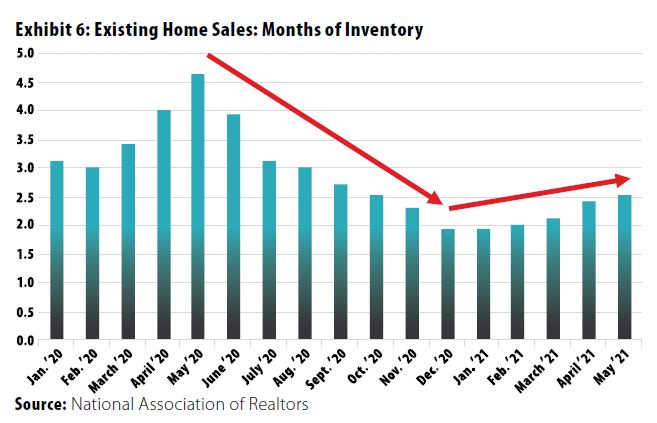

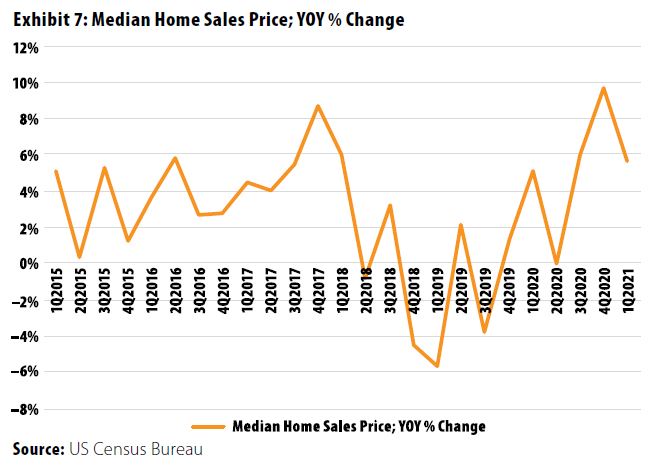

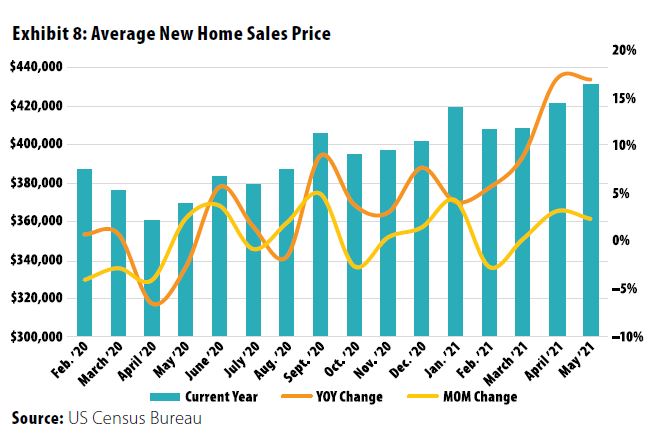

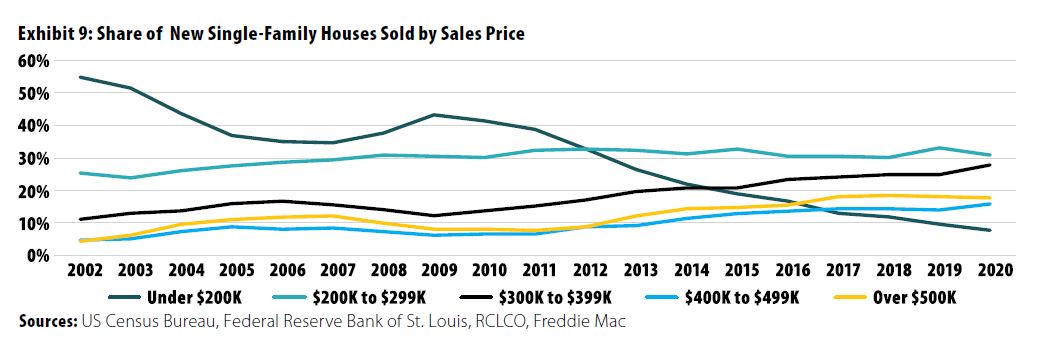

Prior to the pandemic, the new-home market in the US was undersupplied as a result of buyer, builder, and lender caution in the wake of the global financial crisis. After the initial pandemic shutdown eased, consumers responded to being stuck at home with an increased desire for more space in preferred locations, quickly depleting suburban and rural inventories. Low inventories and strong demand led to strong price appreciation. Those high prices have somewhat moderated the strength of housing demand in recent months, although both new and existing home prices are up substantially on a year-over-year basis, and demand remains strong. The inflationary impacts from strong home demand and price appreciation are expected to influence shelter inflation (a component of the Consumer Price Index) through 2022.

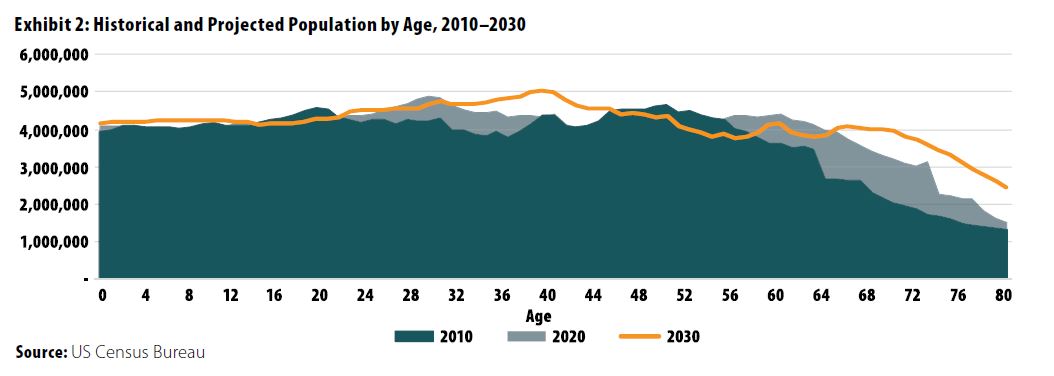

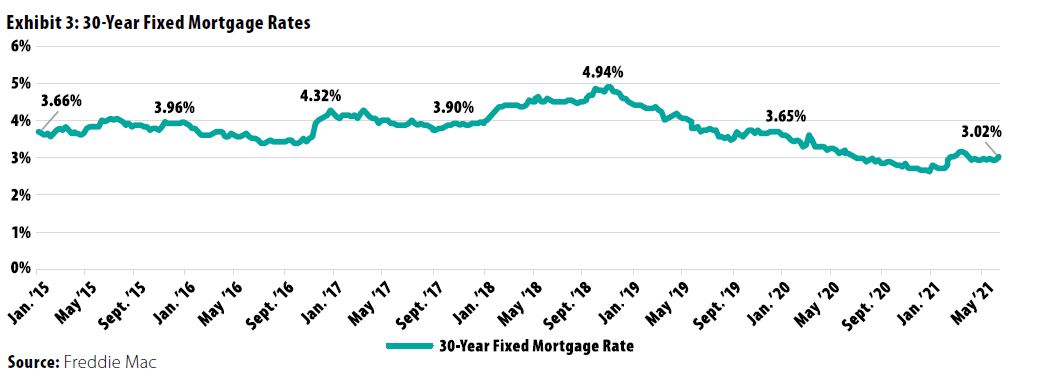

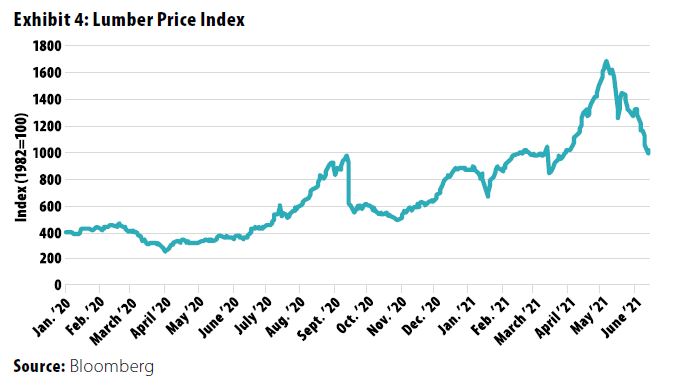

Exhibit 1 summarizes the main factors impacting the US housing market in recent years. Some of these are long-term trends (e.g., demographics), and others are related to the pandemic and likely to dissipate over time.