Walkable Retail: When Old Becomes New Again – Part 2

Americans are returning to walkable neighborhoods. Property values are appreciating much faster in these types of places than they are in car-dependent areas, suggesting people are becoming increasingly willing to pay a premium to live, work, and play in walkable environments.[1] Though widespread today, this focus on walkability has been a growing trend in real estate over the past 20 years, and its impact is particularly noticeable in the case of retail activity.

Retail is an ever-changing industry. To satisfy the evolving tastes and demands of consumers, retailers and retail developers are continually pursuing the latest and greatest shopping experiences. As residents and employers are moving back to walkable neighborhoods, walkability is emerging as a common theme in today’s leading retail shopping. Today, new forms of car-free shopping streets, alleys, and lanes are emerging and thriving.

However, pedestrian-only retail has a mixed record of success. A previous Advisory article recounted the rise and fall of another form of car-free shopping street: the pedestrian mall. Pedestrian malls first emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, when retail was already abandoning traditional urban storefronts for shiny, new suburban shopping malls. In hindsight, sacrificing several blocks of automobile traffic was not a healthy strategy for established shopping streets. Moreover, this approach was not a panacea to save entire downtowns from outward migration to the suburbs, especially at a time when the relative convenience and ease of access of those suburbs were playing a major role in such migration patterns.

However, times have changed for cities, suburbs, and retail. Today, urban places are rebounding. People are moving back to city centers, and employers are relocating to central business districts to take advantage of the talented, well-educated workforce that wants to live and work in the same area.[2] Suburban shopping malls, which traditionally isolated consumers for the sake of convenience, are staid and seem to have fallen out of favor with shoppers. Just as the workplace is changing to attract and retain a talented labor pool, the same people living and working in cities are also looking for unique shopping experiences.[3]

A variety of new forms of pedestrian-oriented shopping streets are emerging as a response. Despite the fact that the majority of pedestrian malls failed, today’s new car-free retail streets are succeeding due to new circumstances and development programs.

In pinpointing the reasons for this disparity, it is important to note that today’s car-free shopping streets are not the same as yesterday’s pedestrian malls. Though pedestrian malls are a type of car-free street, car-free shopping streets are not limited to pedestrian malls, and are—in most cases—entirely different retail products. This article examines the different forms that today’s car-free shopping streets are taking, as well as the reasons for their success.

Types of Car-Free Shopping Streets

In recent years, several new forms of car-free streets have emerged. These streets, lanes, and alleys have materialized across the country, and include shared and intermittent car-free streets, as well as both privately owned streets and streets with multiple property owners.

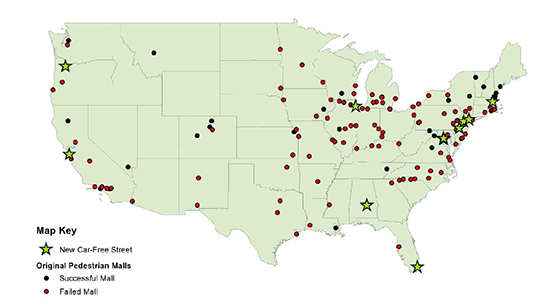

New Car-Free Streets and Original Pedestrian Malls

SOURCE: RCLCO

Shared Streets

Shared streets, while technically not car-free, are nonetheless designed for pedestrian use at certain times. In many cases, these streets are used as fixes to narrow or winding, well-trafficked commercial corridors where sidewalk congestion spills over into the road, creating an unsafe walking environment for pedestrians.[4] Shared streets typically involve one of two approaches. In the first approach, curbs are removed, allowing pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers to coexist in the same, large space. In the second approach, sidewalks are widened, speed limits are decreased, and outdoor features are staged, creating obstacles for cars and requiring them to move at a slower pace.

Shared streets have emerged in many places, and examples include Palmer Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Bell Street in Seattle; and Davis Street in Portland, Oregon. In Chicago, a three-block portion of Argyle Street is in the process of being reconfigured as a shared street, where the speed limit is being reduced to 15 miles per hour and the road is being raised to sidewalk level, so as to create a welcoming, open setting that is supportive of sidewalk cafes and street fairs.

Shared Car-Free Street: Bell Street Park in Seattle, Washington

SOURCE: David Graves, Seattle Parks and Recreation

Intermittent Car-Free Streets

Unlike the pedestrian malls of the 1970s and 1980s, today’s intermittent car-free streets are regular, vehicle-friendly streets most of the time, though closed off to automobiles at specific times, typically during the evenings or on weekends to accommodate additional foot traffic that occurs during those times, while allowing for events such as farmers markets and outdoor films.

Examples of intermittent car-free streets have emerged across the country. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, a one-block portion of Winthrop Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was converted from a shared street to an intermittent car-free street to provide restaurant owners on the street with more space for outdoor seating. Other examples include Ellsworth Drive in Silver Spring, Maryland, and Theatre Way in Redwood City, California, where additional one-block stretches of retail-heavy streets have been closed to automobile traffic at certain times.

Intermittent Car-Free Street: Winthrop Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts

SOURCE: Cara Seiderman, City of Cambridge

Fully Car-Free Streets

Perhaps most similar to the pedestrian malls of the 1970s and 1980s, today’s fully car-free streets are closed off to automobiles at all hours of the day. However, there are two noteworthy distinctions between the car-free streets of today and the pedestrian malls of the past, and these differences pertain to their implementation and location preference.

While pedestrian malls once took over major, commercial thoroughfares, these modern counterparts are being used as components of broader, private developments, or on minor public roads, alleys, and lanes, often as a way to spur foot traffic in underutilized alleys or passageways. In 2008, Bethesda Lane—a one-block, pedestrian-only street—opened as part of the larger, mixed-use project, Bethesda Row in Bethesda, Maryland. Heavily programmed, Bethesda Lane is strategically positioned perpendicular to Elm Street and Bethesda Avenue, two main roads where much of the development is situated. As a result, Bethesda Lane is able to draw users from these main streets, providing them with a quieter, car-free setting that, in many ways, serves as a refuge for passersby. Other versions of privately owned, fully car-free streets have emerged and include Palmer Alley in Washington, D.C.; Liberties Walk in Philadelphia; and Paseo Ponti in Miami.

Private Car-Free Street: Bethesda Lane in Bethesda, Maryland

SOURCE: RCLCO

In a handful of cities, car-free streets are reemerging on commercial thoroughfares with multiple owners, though these spaces still differ from traditional pedestrian malls in that they too are being located on secondary commercial streets where existing automobile traffic is low, setting a mood for more enticing foot traffic. These car-free streets have emerged in Montgomery, Alabama, and Somerville, New Jersey. In Somerville, renovations closed a one-block portion of Division Street to vehicle traffic in 2012, and a majority of residents requested that the change be made permanent. Upon becoming a fully car-free street, retail conditions on Division Street flourished, and first-floor retail occupancy rates more than doubled, reaching 100% within a year.[5] This change is attributable in part to the street’s increased level of activity. Located perpendicular to Main Street, the car-free portion of Division Street now offers outdoor seating and events such as concerts and movie screenings, and— because of its location—it does not disrupt the flow of automobile traffic through downtown Somerville. This is a noteworthy distinction, given that an issue with the original pedestrian malls was that they were inconveniently located. Many of those pedestrian malls were located on main roads, where they traded automobile traffic for pedestrian traffic at a time when an increasing number of Americans were pursuing the more convenient lifestyles associated with the suburbs, sacrificing the convenience of walking for the new pleasures of motoring around.

However, 50 years later, auto dependence is changing, presenting a second distinction between today’s car-free streets and yesterday’s pedestrian malls. Americans are moving back to cities, with all but one of the 25 largest American cities witnessing growth over the last five years.[6] As people return to urban areas, they are showing a preference for walkable neighborhoods, steering away from cars as they trade in drivers’ licenses for public transit fare cards and mobile car-sharing applications. As a result, the number of pedestrians is increasing as the number of drivers is stabilizing, if not decreasing.[7] These trends suggest walkable neighborhoods are better equipped to deal with car-free streets than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Retail follows rooftops, and as Americans move to walkable neighborhoods to fill apartments, condominiums, and office buildings, retailers and retail developers are shifting their attention to the same neighborhoods to take advantage of their growing populations.

Public Car-Free Street: Division Street in Somerville, New Jersey

SOURCE: Beth Anne Macdonald, Downtown Somerville Alliance

Takeaways from Today’s Car-Free Streets

Even in the case of publically operated, fully car-free streets such as the one in Somerville, New Jersey, there are three clear distinctions between the car-free shopping streets of today and the pedestrian malls of the past:

- Timing: When the original pedestrian malls emerged, many Americans were already leaving cities, making it difficult for the malls to attract the visitors needed to sustain themselves. On the other hand, today’s car-free streets are emerging at a time when urban population and employment is increasing in many cities, so car-free streets are well-poised for success.

- Size: Whereas many of the original pedestrian malls were three or more blocks long, nearly all of today’s car-free streets fall under this threshold, with most of the modern counterparts being only a block long. As a result, today’s car-free streets are often less disruptive to the existing flow of automobile traffic, creating space for pedestrians without taking away much space for vehicles.

- Implementation: Unlike the original pedestrian malls, today’s car-free streets are not being pushed as a solution to a crisis; instead, they are an amenity-based positioning strategy, taking the wants and needs of people into account. Today, both public and private car-free streets are being programmed towards the communities they serve. While private car-free streets offer cohesive, carefully selected retail mixes, public car-free streets offer high-demand community events, such as farmers markets, festivals, and outdoor movie screenings. In other words, today’s car-free streets are market-driven, rather than policy-based.

These differences relate to market dynamics. As covered in the previous Advisory article on this topic, economic and social conditions were appropriate in some of the cities where and when the original pedestrian malls first emerged, resulting in a handful of successful malls that continue to thrive today. However, this outcome is the exception rather than the rule. More often than not, the original pedestrian malls were unable to shift consumer and broader locational preferences, which favored suburban shopping malls at the time.

While the original pedestrian malls were an attempt to reverse urban divestment trends, today’s car-free streets are emerging in response to urban revitalization trends. This overarching distinction helps explain why car-free streets are reemerging and succeeding, when pedestrian malls of the past failed.

Today’s car-free streets are creating spaces, while many pedestrian malls got rid of them. When pedestrian malls first emerged, Americans were leaving cities for more automobile-friendly suburbs. By sacrificing road space, the malls removed an urban space that could have been used by the increasing number of drivers, pushing these drivers to the suburbs and weakening downtowns even further as a result. In contrast, today’s car-free streets are an opportunity for communities and developers to repurpose and reposition underused streets, alleys, and lanes.

Car-free streets are perhaps more appropriate than ever. This is particularly true for walkable neighborhoods with increasing jobs and housing. Today, many Americans have grown tired of suburban shopping malls, suggesting there is a clear distinction between “consumerism” and a shopping experience. Successful retail environments now fulfill a variety of needs, and car-free streets offer an interesting and inviting environment not only to shop and eat, but also to live, work, and play, With a careful understanding of market dynamics, developers and communities can find success in creating car-free streets to take advantage of recent trends towards these types of walkable, mixed-use environments, as evidenced by examples that have already arisen across the country.

References

[1] Real Capital Analytics, April 2015, Walking to Higher Value, accessed January 13, 2016

[2] Smart Growth America, Cushman & Wakefield, & The George Washington University Center For Real Estate and Urban Analysis, June 18, 2015, Core Values: Why American Companies Are Moving Downtown, accessed May 9, 2016

[3] N.D. Schwartz, January 3, 2015, The Economics (And Nostalgia) Of Dead Malls, New York Times, accessed May 9, 2016

[4] Commercial Shared Street, National Association of City Transportation Officials, Urban Street Design Guide, accessed May 3, 2016, http://nacto.org/publication/urban-street-design-guide/streets/commercial-shared-street/

[5] Downtown Somerville Alliance

[6] RCLCO analyzed U.S. Census Bureau data from 2010 to 2014

[7] C. Rogers & G. Nagesh, January 20, 2016, Driving Is Losing Its Allure for More Americans, The Wall Street Journal, accessed May 3, 2016

Article and research prepared by Lee Sobel, Principal, and Jacob Ross, Associate.

RCLCO provides real estate economics and market analysis, strategic planning, management consulting, litigation support, fiscal and economic impact analysis, investment analysis, portfolio structuring, and monitoring services to real estate investors, developers, home builders, financial institutions, and public agencies. Our real estate consultants help clients make the best decisions about real estate investment, repositioning, planning, and development.

RCLCO’s advisory groups provide market-driven, analytically based, and financially sound solutions. Interested in learning more about RCLCO’s services? Please visit us at www.rclco.com/expertise.

Disclaimer: Reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the data contained in this Advisory reflect accurate and timely information, and the data is believed to be reliable and comprehensive. The Advisory is based on estimates, assumptions, and other information developed by RCLCO from its independent research effort and general knowledge of the industry. This Advisory contains opinions that represent our view of reasonable expectations at this particular time, but our opinions are not offered as predictions or assurances that particular events will occur.

Related Articles

Speak to One of Our Real Estate Advisors Today

We take a strategic, data-driven approach to solving your real estate problems.

Contact Us