Walkable Retail: When Old Becomes New Again – Part 1

You have probably read the following headline thousands of times, perhaps this year alone: All but one of the 25 largest American cities experienced population growth over the last five years, and an outsized share of these new residents are demonstrating a preference for living in highly walkable downtown neighborhoods.1 The facts on the ground tell us these “post-automobile” households expect high-quality shopping options to fit within their walkable lifestyles, and savvy retailers are desperately looking for storefronts in pedestrian-friendly locations. Today, even the highest-performing suburban retail concentrations share walkability characteristics with their urban counterparts.2

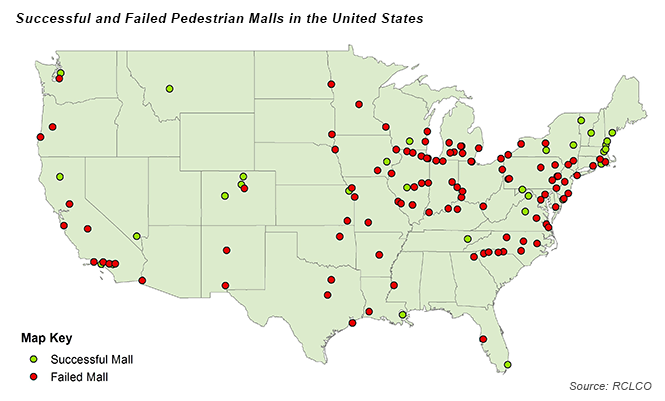

However, there is an inconvenient history to walkable retail, which has a decidedly mixed track record. The ideas behind pedestrian-oriented retail have been tested, and have mostly failed, in the form of the pedestrian malls that dotted American cityscapes during the 1960s and 1970s. So, what is contributing to the success of walkable retail this time around? Similarly to those pedestrian malls that were successful, a strategy based on people, place, and programming is enabling walkable, main street retail to flourish today.

This article is the first in a two-part series examining the lessons learned from a detailed analysis of pedestrian malls, which we believe tells an important tale about the success of urban retail. The future article will discuss how today’s walkable retail is successfully evolving old ideas into version 2.0.

A Look Back to Earlier Pedestrian Malls

Pedestrian malls first emerged in the mid-twentieth century as households and retailers began to suburbanize, leaving those stores and businesses that remained in urban areas to face declining market support. In an attempt to reverse this trend, many cities turned to forms of walkable retail—namely the pedestrian mall—as economic development tools to attract visitors and suburban residents to shop downtown.

A pedestrian mall is best defined as one or more blocks of public streets that are accessible only by foot.3 In many cases, these pedestrian malls were created by closing multiple blocks of main streets with high vehicle traffic and existing retail businesses in locations that had previously been neighborhood or “high street” shopping destinations. This typology emulated suburban shopping malls, which found success with a park-once approach, and sought to mirror these ideas in an urban setting. Of the hundreds of pedestrian malls that emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century, approximately 30 remain intact.

Market Comparison

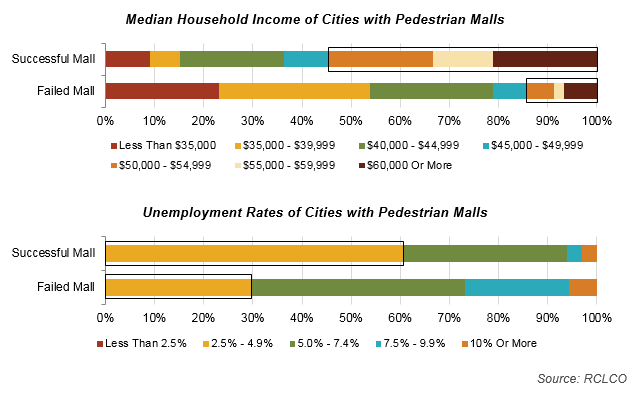

An analysis of over 100 pedestrian malls underscores the importance of economic and social conditions of each local market in determining their success. The relevance of economic and social conditions is intuitive enough, perhaps even obvious, but should not be understated; in cities where residents could not afford or did not want to shop at pedestrian malls, the malls could not sustain themselves on visitors alone.

Economic Factors

In general, pedestrian malls succeeded more frequently in cities with high household incomes and low unemployment rates, highlighting their continuing reliance on local economies to sustain themselves over time, and perhaps the greater appeal of walkability to lifestyle spending, including restaurants, than to shopping for daily needs.

The statistics shown below are current demographics for the cities in which each pedestrian mall is located, which help to evaluate which markets were able to sustain pedestrian malls over the long term.

Median Income: Over 50% of successful pedestrian malls are in cities with a median income over $50,000. Only 15% of failed malls were in cities that met this income threshold.

Unemployment Rates: 60% of successful malls have market areas with current unemployment rates below 5.0%, compared with only 30% for failed malls.

Walkability and Crime Factors

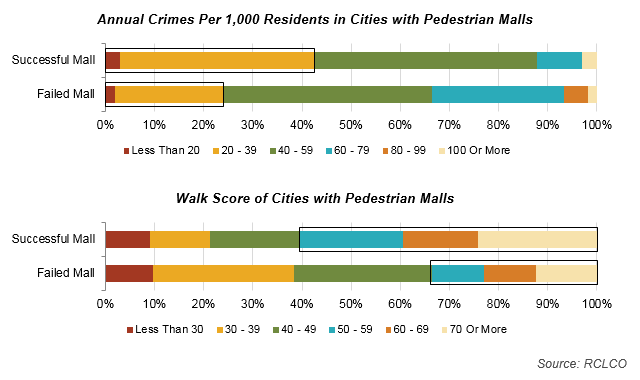

Perhaps somewhat counterintuitively, pedestrian malls succeeded more often in cities with vibrant downtowns, rather than places starved for walkable places, with safety and an existing pattern of shopping in the traditional main street format being other particularly relevant factors. Pedestrian malls failed more frequently in cities with high crime rates and low overall walk scores, likely because high crime rates illustrate uninviting social environments, and low walk scores illustrate sprawling, automobile-dependent ones.

Crime Rates: Twice as many successful malls as failed malls are in cities with a crime rate below 40 crimes per 1,000 residents.

Walk Score: Over 60% of successful pedestrian malls were located in cities with a Walk Score above 50, compared with only 34% of failed malls.

Place-Specific Strategies

However, many pedestrian malls failed even in cities where economic and social conditions were conducive to their success. RCLCO case studies of successful pedestrian malls suggest that, while strong economies and vibrant downtowns likely helped position the malls to succeed, other place-specific strategies were necessary to build off of this foundation.

- The Cooper Avenue Mall benefits from the active, outdoor-oriented lifestyles of people living in and visiting the ski resort town of Aspen, Colorado, both year-round and seasonally. With a substantial cluster of high-end restaurants in addition to aesthetically-appealing design features such as landscaping and outdoor seating, the Cooper Avenue Mall functions as the core of downtown Aspen and attracts both permanent residents and visitors.

- The City of Santa Monica, California, rebranded its struggling pedestrian mall as the Third Street Promenade in 1989, integrating theaters and restaurants. Today, the Third Street Promenade is a premiere entertainment and shopping destination that not only generates new foot traffic, but also capitalizes on existing foot traffic with its proximity to the Santa Monica Pier, which attracts more than six million visitors each year.4

- Similarly, Ithaca Commons in Ithaca, New York, hosts a number of regional festivals and events each year, allowing it to function as the cultural heart of a city which, with two local universities, offers the economic stability needed to support the mall year-round.

Though located in very different regions of the country, these pedestrian malls underscore the role of economic and social conditions in supporting car-free spaces, as well as the influence of other, place-based factors in generating the required level of foot traffic in those spaces.

Where Next?

In general, the analysis found that many cities lacked the market fundamentals needed to support the pedestrian malls that were built there. As such, the failure of pedestrian malls is not directly related to a lack of accessibility or visibility; rather, the failure of the malls stems from the fact that, from an economic and demographic perspective, many American cities were not well-equipped to support pedestrian malls at the time, and a lack of local market support and place-based strategies to generate foot traffic at the malls often accelerated their decline.

Today, the overarching criticism of past pedestrian malls is often that they limited vehicle access, and therefore retailer visibility, at a time when other retail—both urban and suburban—was becoming increasingly vehicle-oriented, with expansive parking lots and signage visible from a great distance. Our research is quite conclusive, however: the critical success factor of those few pedestrian malls that did succeed was not accommodation of the vehicle, but the same factors that underpin the success of walkable main street retail we see flourishing today:

- Strong local market audiences (people);

- Inviting and social gathering places (place); and

- Positioning strategies in the face of broader marketplace settings (programming).

These lessons still apply to urban real estate development today. Now that people and jobs are returning to America’s urban neighborhoods, pedestrian-oriented retail can succeed using place-based strategies to capitalize on underlying economic and market fundamentals.

In recent years, several new forms of car-free streets have emerged, including Bethesda Lane (a component of Bethesda Row, which otherwise is not car-free) in Bethesda, Maryland, and Paseo Ponti in Miami, Florida. Located in both urban and semi-urban environments, these streets are thriving in economically and socially diverse areas, suggesting other factors are playing a role in their performance.

In a future Advisory, we will examine the forces behind the success of these new, car-free streets, and outline the lessons we have learned regarding choosing locations and designing retail environments that are poised for success.

1 RCLCO analyzed U.S. Census Bureau data from 2010 to 2014.

2 Real Capital Analytics. (2015, April). Walking to Higher Value. Retrieved January 13, 2016

3 Pojani, D. (2008). American downtown pedestrian ‘malls’: Rise, fall, and rebirth. Territorio, (46), 173-80.

4 Office of Pier Management, City of Santa Monica

RCLCO provides real estate economics and market analysis, strategic planning, management consulting, litigation support, fiscal and economic impact analysis, investment analysis, portfolio structuring, and monitoring services to real estate investors, developers, home builders, financial institutions, and public agencies. Our real estate consultants help clients make the best decisions about real estate investment, repositioning, planning, and development.

RCLCO’s advisory groups provide market-driven, analytically based, and financially sound solutions. RCLCO’s Urban Real Estate Advisory Group produced this newsletter. Interested in learning more about RCLCO’s services? Please visit us at www.rclco.com/urban-real-estate.

Disclaimer: Reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the data contained in this Advisory reflect accurate and timely information, and the data is believed to be reliable and comprehensive. The Advisory is based on estimates, assumptions, and other information developed by RCLCO from its independent research effort and general knowledge of the industry. This Advisory contains opinions that represent our view of reasonable expectations at this particular time, but our opinions are not offered as predictions or assurances that particular events will occur.

Related Articles

Speak to One of Our Real Estate Advisors Today

We take a strategic, data-driven approach to solving your real estate problems.

Contact Us